Tuesday, April 15, 2014

An updated Elwha river mouth timelapse

Monday, April 7, 2014

Tracking shorelines

The map above motivates me. This is a screen grab from the NANOOS Beach and Shoreline Change site, showing shoreline monitoring sites in Washington State. Kudos to NANOOS for including data on shoreline change in their incredible site (which is a compendium of all things related to oceanography data) - but the map makes it clear that we in Washington State are dropping the ball when it comes to understanding trends related to shoreline morphology.

Proposed locations of shoreline monitoring on the Olympic Peninsula

As part of my program I've proposed and am developing a small scale shoreline monitoring program for the Olympic Peninsula. Why small-scale? Well because its just me, and this is a big area. But something is better than nothing. Working with a bunch of partners (Olympic National Park, the Quileute Tribe, the North Olympic Peninsula Skills Center Natural Resources Program, the Quilayutte Valley School District, Pacific Coast Salmon Coalition, the North Pacific Coast Marine Resources Committee, US Coast Guard, the Jamestown S'Klallam Tribe, the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe and the US Fish and Wildlife Service) I've been able to either start developing or collecting data on a bunch of the proposed sites in the map above.

The partnership with the QV School District, the Skills Center, the MRC and the Pacific Coast Salmon Coalition is particularly valuable because it has allowed us to get students involved:

Students surveying Rialto Beach, Olympic National Park

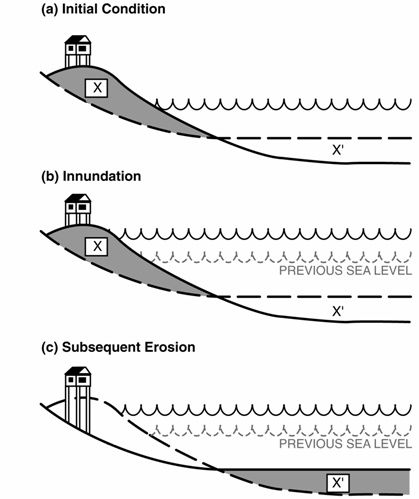

A growing body of evidence supports the idea that engagement in research experiences early in students' academic career provides positive benefits, so this is a great opportunity to use this program to support Olympic Peninsula students. Why do it at all though? Well - my primary motivation regarding monitoring shoreline morphology is that we expect shorelines to change in increasingly unusual ways due to climate change. Here, for example, is a schematic describing one model of how shorelines respond to sea level rise:

In general, we expect shorelines to move landward under rising seas, and this will likely be associated with steepening and coarsening of the beach. This has all sorts of ecological implications - but my primary motivation here is how that will change the beach's protective capacity. Beaches are barriers - protecting human communities from the ocean, and it is likely going to become more difficult for beaches to provide those buffering services to communities in the coming decades.

The figure above is from an analysis of climate-related vulnerabilities for the Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary, and is designed to show the potential change to the water level histogram (this is the distribution of all water levels that the coast experiences over a longer time period...like a few months or more) due to both sea level rise, storms and changes to the outer coast wave climate. The point is that under climate change projections, the upper part of the beach will come into contact with the ocean much more frequently, which could promote flooding and erosion.

However, one thing is already clear from working on the outer coast...beaches change dramatically all of the time:

Above, for example, are two beach profiles from Rialto Beach, one collected in the Fall of 2012 and the other in the spring of 2013. These (preliminary) data suggest that over the winter the beach built outwards by ~10 m! For those that know this coast this is hardly surprising, indeed there is significant beach change observable in the much shorter record captured by this time lapse video shot around Mosquito Creek (this was shot to document the removal of the Misawa Dock associated with the Tohoku tsunami debris). But characterizing the rates and patterns of change in advance is crucial to being able to pick out erosion signals that are unusual in the future.